Recursion is fascinating.

I had the idea to make a song that would also function as a computer program with which the song could be played, or alternatively make a computer program that would be able to transform its own zeros and ones into music. That project did not end with a satisfactory result, neither in terms of music nor programming.

I also had an idea to make electronic music, which in principle would sound the same when played at significantly different speeds. This would work in a similar way as those images which repeat themselves when zooming in on them. That project actually worked, but not very well artistically.

This song is an experiment of using the program that plays the song as an instrument in the song. Of course I had to cheat somewhat by cutting the program into pieces and stretching and compressing its waveform.

The song was created in connection to a brothel-themed party at my student residence. Hence the title.

The ideal passenger

I may be the ideal passenger. I believe I passenge better than most.

Garden of your mouth

As an ambitious physics student, I naturally got the idea to compose a song connected to each relevant example in the textbooks. The first of these songs was made to illustrate “The Astronauts’ Tug-of-war” from the introductory course in mechanics. The chords in the song were of course mostly experimental because of the topic of the example, and the lyrics were initially taken straight from the textbook. However, the words soon had to be changed in order to fit the melody, and the theme of the text degenerated into something more pessimistic than two astronauts tied together by a rope in outer space: the complete disparity between the expectations and the realities of modern life. When the song, which was now a piano ballad, was finished after several weeks of hard work, the theme was no longer relevant and I decided to never make another physics textbook example song.

One year later I squeezed the song into my Amiga, and it turned into this simple pop tune.

Brysk tundra

I once asked myself what kind of music a lemming would create. Since lemmings are energetic but not very intellectual creatures, the main focus of the music would be on the beat, not on the melody, the harmonies or even the rhythm. Naturally, the lyrics would mostly be about living in the harsh conditions in the wilderness up north. This tune was my attempt to emulate the music of the lemmings.

I have now moved to the land of the lemmings, and now I know how wrong I was.

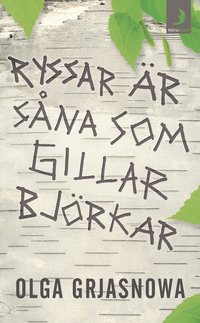

Ryssar är såna som gillar björkar

Ryssar är såna som gillar björkar är Olga Grjasnowas debutroman. Boken handlar om den unga kvinnan Masja, som i början av boken lever tillsammans med fotografen Elias i Frankfurt och utbildar sig till tolk. Plötsligt ställs hela hennes värld på sin ända och man får följa hur hon tar sig igenom krisen. Samtidigt får man via tillbakablickar insyn i det trauma som Masjas uppväxt som judinna i Azerbajdzjan under de värsta åren av konflikten med Armenien fört med sig.

Boken är läsvärd. Framför allt har författarinnan lyckats så pass väl att fånga stämningen i miljöbeskrivningarna att det ofta känns som att vara på plats själv. Även personerna känns verkliga, med ett viktigt undantag: huvudpersonen själv (Misja). Det är, framför allt mot slutet av boken, emellanåt svårt att förstå varför hon gör det hon gör. Överhuvudtaget känns det som om handlingen i boken tappar farten mot slutet, som dessutom kommer ganska plötsligt. Men överlag är det en riktigt bra bok som jag kan rekommendera att läsa.

Boken inleds med ett bra driv,

Jag ville inte att den här dagen skulle börja. Jag ville ligga kvar och sova vidare, men genom de vidöppna fönstren trängde skratten från grönsakshandlarna och skramlet från spårvagnarna in. Vår lägenhet låg inte långt ifrån centralstationen, vilket framförallt innebar att det i vår stadsdel fanns hela kvarter som man helst undvek, fulla med lågprisaffärer och jättelika porrbiografer. Här, mellan en kinesisk kemtvätt och ett alternativt ungdomscenter, vars besökare regelmässigt urinerade i vår port, bodde vi.

vilket snabbt sög in mig i berättelsen.

Saxofonen Rune

I have had the ambition for a very long time to make a film with the name “Moments of inertia”. It is supposed to be very ‘artistic’, containing long scenes with people waiting at railway stations, airports, dentists, unemployment offices and similar places. Such a pretentious film requires a soundtrack with a piano playing arbitrary harmonies so I started playing with some notes on the piano. After a while the progression of notes became too complicated for my abilities at the piano forcing me to use the computer to actually hear how the song would turn out. Hence I made this little tune on my Amiga computer.

The song was supposed to be the background music at a scene with a saxophone in a music shop.